(I) Our artist in heaven

"All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned." ~ Karl Marx

Art is the religion of the secular kind. It tames the mind, guides the spirit and kindles community for the atheist and the agnostic in much the same way as scripture would for the rest. Art tempers our emotionality, our morality and our aesthetics, becoming for the lost, a guiding light in trying times. And so, we do to good art what the religious do to myths, legends and messiahs. In awe and surrender, we raise it so high above us that it gets out of our reach. The more an art appeals to our senses, the more we thrust it toward the skies so no one may touch it, taint it or turn it inside out. What's meant to serve us becomes so sanctimonious that us not serving it becomes sacrilegious.

We adorn our rooms, screens and imaginations with our favorite artworks. We curate our lives around art that speaks to us. We cosplay as our favorite characters, and in these lush gardens of our curations, we build mental temples to house the artists we adore, to thank them for blessing our lives with their conjurings. The artist becomes the priest, that special human ordained to grant us access to the heavenly abodes of our one true god, the holy piece of art. To this artist we concede a part of our self, and with it, our ability to make their art our own. And to this artist, we then kneel and pray to give us their next gift. Which they do.

And then, one day, out of nowhere, storms into this pious temple, without invitation, without courtesy, the suited booted capitalist. He shoves the priest aside, yanks off the idols, and begins parcelling the pillars, the flooring and the roof, making them his own piece by piece. We watch as the capitalist attaches exchange value to the art, shareholder value to the pillar and propaganda to the roofs and flooring. We gape as the artist-priest prostrates for survival, or scurries out of view, disgracing our own prostration to them just moments ago. Slowly but steadily we watch as our emotionalities, sensibilities, and subjectivities are all forced to come to terms with their relentless commodification. Sooner than later, the capitalist desecrates all that we love for a better quarterly report. He sullies our irrational romanticism for his logical rates of profits. He bulldozes our madness to make space for his methods.

(II) Thy will be done

“If the Luddites have taught us anything, it’s that robots aren’t taking our jobs. Our bosses are.” ~ Brian Merchant

The luddites get a bad name. In their mythologized form, they are the movement of workers in nineteenth century England that protested against the introduction of new technologies by breaking machines and burning factories through organized riots. The term 'luddite' is now used to slander anyone who opposes any new industrial breakthrough that shakes up the way things are being made. While the actual luddite movement was not so irrational in its hate of machinery (targeting either only unsafe machines, or all machines only to symbolically place dignity of labour over lifeless property), the introduction of new technology has always throws off a section of people in every era, and this tendency is now commonly associated with the term luddism. Those who oppose AI generated art (if they even call it that) are often called luddites by their critiques. The goal is to present their opposition to AI as primitive and futile in history's long march towards automation.

The mythologized luddite spirit in us working classes yearns to go back to a simpler era. Our souls seek the simplicity of nature's freedoms and bounty. It laments the loss of mystery, of beauty, of liberty with the onslaught of technology, much like what is found in Hayao Miyazaki's movies. But while his art can appeal to us emotionally, capitalism forces us to grasp the real desecration of our emotions that it has brought forth. It forces us to confront the ruins of our temple of subjectivities, to face our inherent helplessness in preventing economic forces much bigger than us from ravaging all we hold dear. And in confronting this unfolding arch of history, it turns out that luddite rage is too inefficient, too insincere.

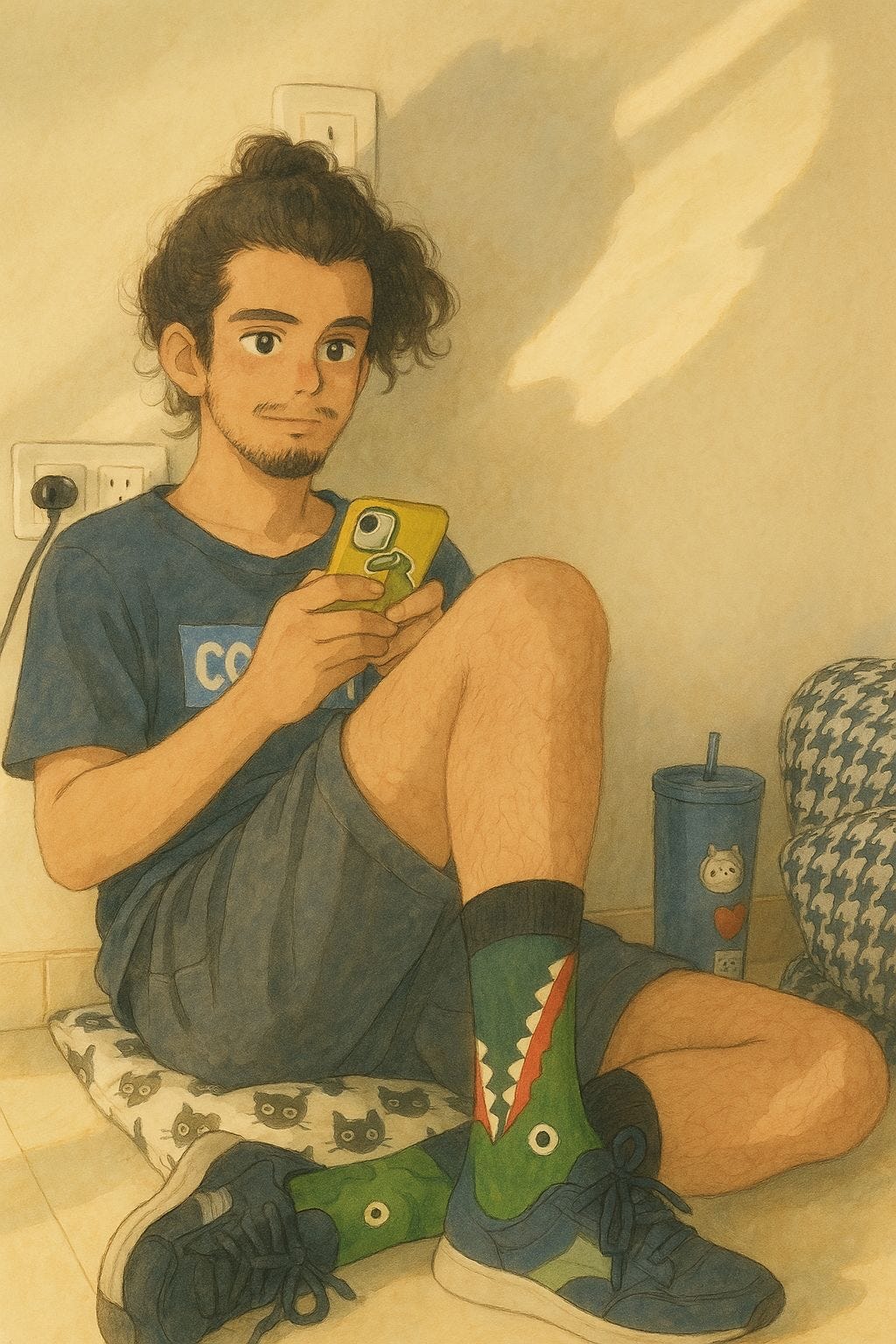

As I write this, internet has been flooded with AI generated ghiblified images. People are divided over the ethics of it all. Miyazaki is said to have called AI an insult to life itself. While he was referring to a specific AI generated video that was quite abhorrent and scarring compared to his earthy and fantastical style of animation, we can be sure he isn't a fan of using AI to create art, considering Ghibli studios largely does hand-drawn animations. Given all this, generating AI images in a style pioneered by him is being seen as a sign of disrespect to him, not to mention theft of his intellectual property. In general, AI generated images are being called soulless slop.

Two things must be understood to fully root oneself in this debate. First, modern capitalism is doing to art and knowledge what seventeenth century capitalism was doing to land and goods: forcefully turning socially-held commons into a few individuals' private means of production. If you're a European, most of your ancestors learnt this the day all the land they held, owned and worked on in commons was privatized by some scheming industrialist with the help of the rulers of his time. These formerly free ancestors were then kicked out of these lands that used to feed them, and then forced to sell their labour at the industrialist's brand new factories set up on those very lands. If you're an Indian, most likely your ancestors learnt this the day the British chopped off their thumb or broke down their handlooms, to forcibly crush the thriving textile and other industries they were self-employed in. The history of capitalists is nothing but a history of them appropriating social tools in order to privatize outputs, leaving non-owners with nothing to sell but their own time and labour. Second, american capitalists, in order to reduce their costs, are trying to automate the only high-paying employment they have left ever since they shifted manufacturing to Asia: white-collar service sector jobs mainly in hollywood, finance, research and consulting.

Much like with the serfs who were kicked off their lands or the weavers whose thumbs were chopped off, today's artists and art devotees facing the spectre of unemployment and uncertainty are sure to be attracted to luddism as a form of resistance. But much like luddism of the past centuries, this resistance won't survive the tide of historic forces either. We are destined to eventually move towards the automation of all labour, including of the production of knowledge and art. The luddites can only delay this trend, gaining small wins in the short term that will be inevitably rolled back any way.

(III) On earth as it is in heaven

"Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt." ~Leonardo da Vinci

Can you identify 'soulless AI slop' from soulful art created by humans? In this test of 11,000 people, which you can take here, most people couldn't. In fact, most people who said they hated AI art ended up unknowingly picking AI generated art as their favorite of all the pieces they had been shown.

Turns out, whether we are yet ready to accept it or not, the idea of 'soul' in art has much less to do with the artist and much more to do with us, the observer, projecting our self into what we're seeing. We have spent so much of our lives worshipping artist-priests for delivering to us these portals of sense and subjectivity that we call art, that we have forgotten our own selves as the mediums that add any real value to what the artist creates. Art speaks to us, seems to have a soul to us, firstly because it exists courtesy the artist, but then more importantly because we are the ones who witness it, we are the ones who seek meaning in it. We find in it what we cannot find outside it, and in this process, we project the missing part of our soul into it, to seek completeness with it. Art becomes art when we stop needing the artist-priest to supervise our interaction with it, when we can be alone and feel seen with this secular divine.

To accept that isn't to diminish the skill, craft and vision of the artist, but it is to either bring down the artist from the heaven-temples we've placed them in, or better, it is to join them as fellow equals in the heavenly-abode of their creations. It is to separate the art from the artist, not as an authoritative capitalistic appropriation of their labour, but as a democratic internalization of the art as an extension of us as much as the artist. It is the process not of trying to undo capitalism, like the luddite spirit, but of trying to surpass capitalism by socializing all knowledge and art as public human heritage. Hidden behind IPs and patents is nothing but class, hierarchy and priesthood of artists and scientists. A true sign of modern civilization would be the free access to all knowledge and culture, and the ability to produce it.

A challenging four-second scene in Studio Ghibli's 'The Wind Rises' took their animator Eiji Yamamori fifteen months to complete, because Miyazaki was adamant that every frame of the animation must be hand-drawn and not computer generated. I could appreciate his love and dedication for the craft of hand-drawn animation much more if Miyazaki was illustrating his works himself. But since he acts as the director, employing animators based on his vision, I do not think the animators he employs are freer to follow their passions than any other worker in any other production house. Executing with your own labour someone else's vision can be excruciating when other more efficient ways of doing things exist but are not allowed to you. Especially since a viewer can't make out a good CGI animation from a hand drawn animation (and now even AI generated art from CGI art). I don't intend to be harsh on Miyazaki here. But I am trying to present a perspective that is possible by skipping subordination to the artist-priest, by critiquing and analyzing as human the one who brings us the bounty of his vision.

I don't mean to say that art forms shouldn't be protected either. The craft of making Malmal Khas, a special fabric woven in eighteenth century Dhaka, which was so soft and delicate that entire sarees of it could allegedly be folded into a matchbox, has been completely lost to time. British colonialism and industrialization are to blame. Any particular loss of art, craft and heritage is a universal loss of our story of humanity too. Rather, what I mean to say is that till the class system exists, till one person works for the other to survive, the automation of all forms of labour must be encouraged and understood strategically as a milestone in our path to collective liberation. And to not lose sight of the goals of this liberation, we must keep in check our tendencies of catapulting other people to class-heavens outside our reach.

Once all work has been automated, and grains, clothes and goods are being sustainably produced in collectively-owned self-running factories, humans will be freed from all labour. A classless, stateless, moneyless society, an earthly commune will be so created. For the first time in the history of this universe, humans will then be able to choose between endless leisure, research and creating art, and it wouldn't matter whether they go about it with AI, machines or bare hands. But till then, we must resist surrendering to subjective hierarchies, allow the march of soulless slop, keeping our eyes on the price: collectivizing all means of production, including of the production of art, to soon liberate art and ourselves.

PS: even though these opinions are presented strongly and firmly, these may be far from my final thoughts on this topic. The world of AI is evolving very fast, and the discourse around it even faster. As newer perspectives emerge from more and more stakeholders, my understanding will evolve too. In the meantime, I would love to know your thoughts!